What Are Wildlife Corridors?

Wildlife corridors are natural movement routes that allow animals to travel between protected areas and surrounding landscapes in search of food, water, breeding grounds, and seasonal refuge. In savanna ecosystems, corridors are not optional extras—they are ecological infrastructure that keeps wildlife populations viable.

For Nairobi National Park(NNP), wildlife corridors are especially critical because the park is small, unfenced on only one side, and embedded within a rapidly expanding metropolitan region.

Why Nairobi National Park Depends on Corridors

Nairobi National Park covers ~117 km², making it one of the smallest national parks in Africa. While it supports an impressive diversity of wildlife—lions, leopards, rhinos, buffalo, giraffes, and hundreds of bird species—the park cannot function as a closed ecological system.

Key realities:

- The park cannot sustain large herbivore populations year-round without access to external grazing areas

- Seasonal rainfall variability requires animals to track grass and water beyond park boundaries

- Predators depend on prey that moves in and out of the park

Without corridors, the park risks becoming an ecological island, leading to:

- Overgrazing

- Increased predation pressure

- Higher disease transmission

- Long-term population decline

The Southern Corridor: Kitengela Dispersal Area

Location and Scale

The only functional wildlife corridor for Nairobi National Park lies to the south, across the Mbagathi River, opening into the Kitengela rangelands.

This area forms part of the wider Athi-Kaputiei Plains, a historic seasonal range used by wildlife long before the park was gazetted in 1946.

Approximate spatial context:

- Nairobi National Park (core): ~117 km²

- Kitengela rangelands: ~390–450 km²

- Athi-Kaputiei ecosystem: ~2,200 km²

How the Corridor Works Ecologically

Seasonal Movements

- Wet season (March–May):

Wildebeest, zebra, gazelles, and eland disperse south into Kitengela for calving and fresh pasture - Dry season (June–October):

Wildlife returns to Nairobi National Park, which acts as a dry-season refuge

This pattern:

- Reduces grazing pressure inside the park

- Maintains grassland productivity

- Supports predator–prey balance

Land-Use Change: The Core Threat to Corridors

What Has Changed in Kitengela?

Since the 1980s, the Kitengela area has experienced rapid land-use transformation, driven by:

- Subdivision of Maasai group ranches

- Sale of land to non-pastoralists

- Urban expansion from Nairobi

- Infrastructure, industry, and agriculture

Quantified Land-Cover Change (1984 → 2010)

Research shows dramatic shifts:

- Grassland: −54.13%

- Riverine vegetation: −81.63%

- Built-up / tarmac areas: +261.40%

- Farmland: +18,495%

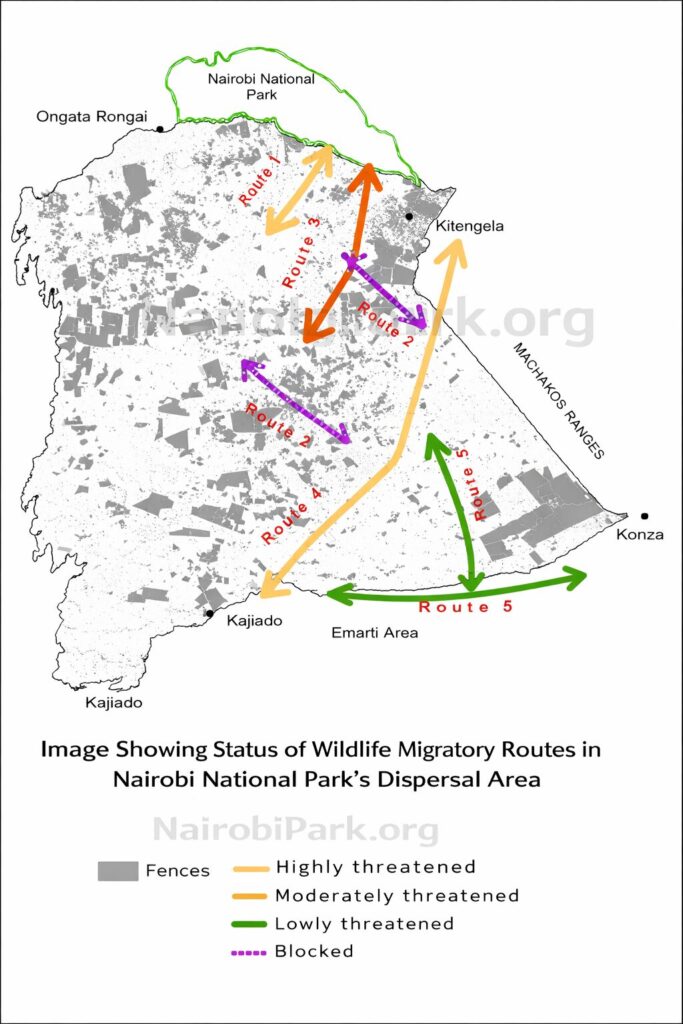

These changes have physically blocked migratory routes through fencing, settlements, quarries, and roads.

Ecological Impacts on Nairobi National Park

When corridors shrink or fragment, the consequences are measurable:

1. Wildlife Confinement

Animals increasingly remain trapped inside the park, unable to reach wet-season grazing and calving grounds.

2. Population Declines

Studies document steep declines in migratory ungulates, particularly wildebeest, whose regional numbers collapsed from ~30,000 in the late 1970s to ~5,000 by the 2010s.

3. Increased Human–Wildlife Conflict

Blocked corridors push wildlife into closer contact with farms and settlements, increasing:

- Livestock predation

- Crop damage

- Retaliatory killing of predators

4. Altered Game Viewing Patterns

For visitors, this means:

- Higher wildlife densities near the southern park boundary

- More sightings concentrated in fewer areas

- Less natural movement across the broader landscape

The Land Lease Solution: Keeping Corridors Open

The Kitengela Wildlife Conservation Land Lease Program

In response to corridor loss, conservation partners launched the Kitengela Wildlife Conservation Land Lease Program in 2000.

Core idea:

Pay landowners to keep land open for wildlife movement instead of fencing, farming, or selling it.

Key features:

- Landowners receive ~US$4 per acre per year

- Contracts prohibit fencing, subdivision, cultivation, or quarrying

- Wildlife-compatible livestock grazing is allowed

Results by 2012

- ~60,000 acres secured under conservation leases

- 417 households participating

- US$837,000+ paid directly to landowners

- Lion use of Kitengela increased from ~18 to 35+ individuals

- Education outcomes improved, with most payments supporting school fees

This program is widely cited as a global model for Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) in savanna landscapes.

Why Corridors Are the Key to Nairobi National Park’s Survival

Nairobi National Park’s future does not depend only on what happens inside the fence.

It depends on:

- Whether wildlife can still move south

- Whether Kitengela remains open rangeland

- Whether land-use planning prioritizes ecological connectivity

Without functioning corridors:

- The park becomes over-managed and artificial

- Wildlife populations decline

- Conservation costs increase dramatically

What Must Happen Next

To secure Nairobi National Park’s wildlife corridors:

- Protect remaining open land in Kitengela

- Scale up land lease and conservation easement programs

- Enforce land-use zoning under county planning frameworks

- Share tourism benefits with corridor landowners

- Integrate corridors into national infrastructure planning

Final Takeaway

Nairobi National Park is not just a park—it is the core of a much larger ecosystem.

Its wildlife corridors, especially through Kitengela, are not optional extras but the lifelines that keep the park alive.

Protect the corridors, and Nairobi National Park thrives.

Lose them, and the park becomes an island.