Introduction

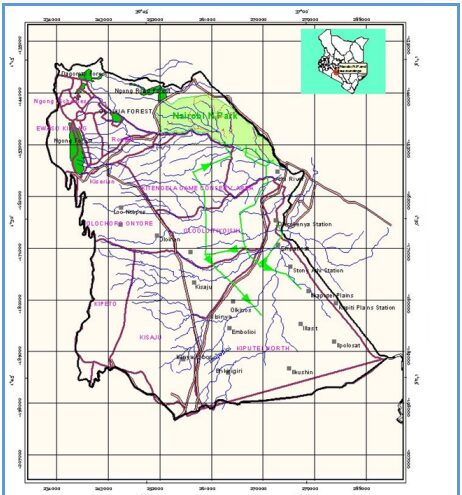

The Athi-Kapiti Ecosystem (AKP) is a vast savannah landscape covering approximately 2,200 km² and forms a crucial ecological region in southern Kenya. Nairobi National Park (NNP) is a core part of this ecosystem, which extends from the Rift Valley escarpment in the west to the Konza-Magadi Railway in the southeast.

Historically, the indigenous Maasai pastoralists have coexisted with wildlife in this region for centuries, utilizing the rich grazing lands while allowing herbivores and predators to thrive. Before European colonization in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Athi-Kapiti plains boasted one of the most spectacular and largest concentrations of wild animals in East Africa. However, increasing human activity and urban expansion have significantly altered the landscape, posing major conservation challenges.

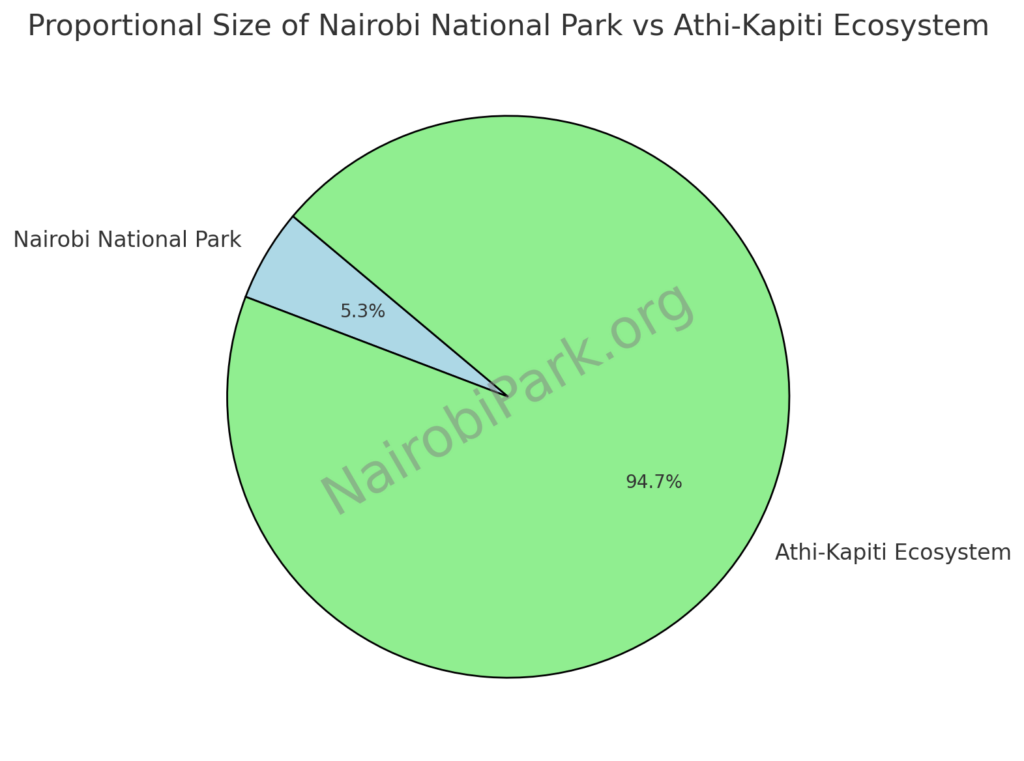

The Athi-Kapiti Ecosystem spans approximately 2,200 km², with Nairobi National Park (NNP) covering 117 km², accounting for just 5.3% of the total ecosystem. This stark metric highlights the park’s heavy reliance on the surrounding 94.7% of open rangelands as a vital dispersal area for migratory wildlife.

Historically, the Athi-Kapiti plains supported one of East Africa’s largest wildlife concentrations, but rapid urbanization, land fragmentation, and infrastructure projects have significantly reduced available habitats. The seasonal migration of herbivores, such as zebras and wildebeest, plays a crucial role in maintaining ecological balance, yet their movements are increasingly restricted.

The pie chart visualization above reinforces the disproportionate land distribution, underscoring the urgent need for conservation measures. Ensuring wildlife corridors remain open, supporting community-led conservation initiatives, and implementing sustainable land-use policies are critical to preserving this fragile yet vital ecosystem before further habitat loss undermines its biodiversity.

Geographic and Ecological Features

- Total Area: ~2,200 km²

- Boundaries:

- West: Rift Valley Escarpment

- Southeast: Konza-Magadi Railway

- Landscape: Open savannah, seasonal wetlands, rolling plains, acacia woodlands, and rocky outcrops.

- Climate: Semi-arid, characterized by bimodal rainfall (long rains: March-May, short rains: October-December).

- Hydrology: Major rivers include Mbagathi River (Nairobi National Park’s natural boundary), Athi River, and Stony Athi.

Wildlife and Migration Patterns

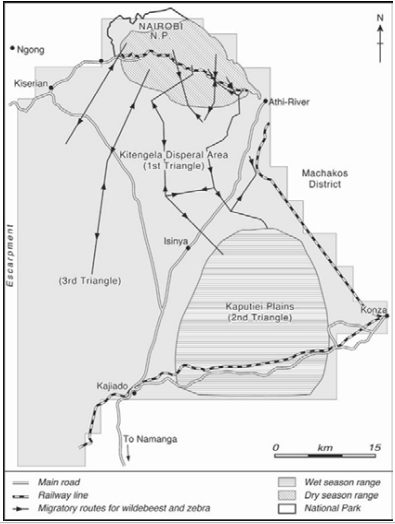

The Athi-Kapiti ecosystem serves as a critical wildlife migration corridor. Animals follow an annual migration pattern driven by rainfall and food availability. The wet season allows large herbivores to disperse into the surrounding plains for breeding, while the dry season forces them back into Nairobi National Park as a refuge.

Historical and Current Trends:

- 1970s Wildebeest Population: ~30,000 (Ogutu et al. 2011).

- 2011 Census Wildebeest Population: <4,000 (DRSRS 2011).

- Migration Sequence:

- Zebras leave NNP first at the onset of rains.

- Followed by wildebeest and other herbivores moving to the southeastern plains.

Mammals:

- Large Herbivores: Wildebeest, zebras, Maasai giraffes, elands, hartebeests, buffalo.

- Big Cats: Lions, leopards, cheetahs.

- Small and Medium-Sized Mammals: Warthogs, jackals, servals, hyenas, dik-diks.

- Rare Species: Fringe-eared oryx, African wild dogs (occasional sightings).

Birds:

- Over 400 recorded bird species, including secretary birds, ostriches, and martial eagles.

- Wetland and grassland birds thrive in the seasonal ponds and savannahs.

Flora:

- Dominant Vegetation: Savannah grasses (Themeda, Pennisetum species), acacia woodlands.

- Riverine Vegetation: Found along Mbagathi River, providing habitat for birdlife and small mammals.

Conservation Significance

The Athi-Kapiti Ecosystem is part of the Southern Rangeland Conservation Zone, classified by the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) as a critical area for the protection of endangered species. The six interconnected sub-ecosystems in this conservation area include:

- Serengeti-Mara Ecosystem

- Nairobi-Athi-Kapiti Ecosystem

- South Rift Ecosystem

- Amboseli-Kilimanjaro Ecosystem

- Tsavo-Mkomazi Ecosystem

- Greater Lake Naivasha-Elementaita-Nakuru-Eburru Ecosystem

The survival of Nairobi National Park depends on maintaining open rangelands for wildlife migration. The Maasai landowners who bear the social and economic costs of wildlife conservation play a key role in preserving these corridors.

Major Conservation Challenges

1. Urbanization and Infrastructure Development

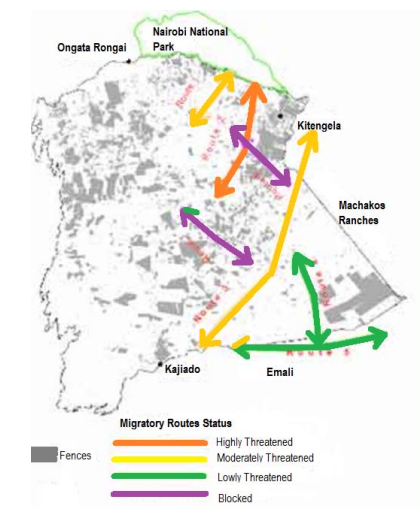

- Nairobi’s rapid expansion, alongside the growth of Kitengela, Isinya, and Athi River towns, has led to habitat fragmentation.

- The Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) and other road networks cut across migration routes, limiting wildlife movement.

2. Land Subdivision and Habitat Loss

- Traditional Maasai communal lands have been privatized and fenced, restricting herbivore migration.

- Increased human settlement has resulted in the conversion of rangelands into residential and agricultural areas.

3. Human-Wildlife Conflict

- Predators such as lions attack livestock, leading to retaliatory killings by pastoralists.

- Crop raiding by herbivores further fuels tensions between local communities and conservationists.

4. Climate Change and Resource Scarcity

- More frequent droughts and erratic rainfall patterns reduce pasture and water availability.

- Shrinking water sources lead to increased competition between wildlife and livestock.

Conservation Efforts

Government and Institutional Initiatives

- Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) manages Nairobi National Park and monitors wildlife migration.

- Zoning Policies aim to regulate land use and protect wildlife corridors.

Community and Private Conservation Efforts

- Kitengela Wildlife Conservation Lease Program: Pays landowners to keep land open for migration.

- Private Conservancies: Kapiti Plains Research Station, Olerai Conservancy, Enkop-Kitengela Conservancy.

- Eco-tourism ventures that provide revenue for conservation and local communities.

Sustainable Solutions and Recommendations

- Strengthening Wildlife Corridors: Ensuring connectivity between Nairobi National Park and the southern rangelands.

- Expansion of Conservation Leases: Increasing participation in the Kitengela Wildlife Conservation Lease Program.

- Better Urban Planning: Enforcing zoning regulations to prevent encroachment on key wildlife habitats.

- Water Resource Management: Establishing artificial waterholes to supplement natural rivers during dry seasons.

- Community Involvement: Encouraging sustainable eco-tourism and conservation-friendly land use.

Conclusion

The Athi-Kapiti Ecosystem is a lifeline for Nairobi National Park and a crucial component of Kenya’s southern conservation region. Despite increasing human pressure, sustainable conservation efforts, community engagement, and policy-driven interventions can help ensure its long-term survival. The region’s importance as a wildlife dispersal area, biodiversity hotspot, and buffer against urban expansion makes it a priority for conservationists, government agencies, and local communities alike.

The Loss of Wildlife Corridors and Its Impact on Nairobi National Park

The viability and future of Nairobi National Park (NNP) are increasingly under threat due to the rapid loss of wildlife corridors in the Athi-Kapiti ecosystem, particularly on the southern boundary, where the park remains unfenced. At 117 km², NNP is too small to sustain its wildlife populations year-round, necessitating seasonal migration to the Kitengela dispersal area and the broader Athi-Kapiti plains. These open grasslands, historically used by Maasai pastoralists and wildlife alike, once formed a crucial migratory path extending southwards to the Serengeti in Tanzania. However, rapid urbanization, land subdivision, and infrastructure expansion have severely disrupted these critical pathways, leading to increased habitat fragmentation, human-wildlife conflict, and population declines of key migratory species such as wildebeest and zebra.

Urbanization and Land Subdivision: A Major Conservation Challenge

The southern lands of NNP, once vast and open, are now being rapidly subdivided, fenced, and sold for suburban development, driven by Nairobi’s urban expansion. The Kitengela dispersal area, situated adjacent to the park, has become an attractive location for residential and commercial development, pushing land values to record highs. Many Maasai landowners, facing economic pressures, have opted to sell their lands, permanently closing off traditional wildlife pathways.

This has led to a physical and ecological blockade, making it nearly impossible for wildebeest, zebras, and other herbivores to access grazing lands beyond the park, which they historically relied upon during the wet season. The annual wildebeest migration, which once extended from NNP through the Athi-Kapiti plains, has suffered drastic declines, with numbers plummeting from 30,000 in the 1970s to fewer than 4,000 by 2011.

Additionally, major infrastructure projects, including the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR), expanding highways, and commercial developments, have further fragmented the landscape. While some wildlife underpasses were included in the SGR project, many species avoid using them due to noise, artificial structures, and increased human presence. The consequence is a severely disrupted ecosystem, where wildlife is confined to shrinking, isolated habitats, increasing competition for food and water while exacerbating human-wildlife conflicts as predators and herbivores encroach on human settlements.

Conservation Interventions: Mitigating the Loss of Wildlife Corridors

In response to these escalating threats, multiple conservation initiatives have been launched to maintain open rangelands and reduce human-wildlife conflict. Some of the most notable include:

- The Wildlife Conservation Lease (WCL) Program – A Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) initiative where Maasai landowners are financially compensated to keep their land unfenced, preventing habitat fragmentation. Initially met with skepticism, the program has gained wider acceptance, with participating households receiving USD 400–800 annually depending on land size.

- The Lion Lights Program – A community-driven initiative that installs solar-powered bulbs around Maasai bomas (livestock enclosures) to deter lion attacks on livestock, reducing retaliatory killings of predators.

- Livestock Compensation Scheme – Provides financial compensation to herders whose livestock has been attacked by lions and hyenas, fostering tolerance for predator conservation.

- The Kitengela Land Use Master Plan – A zoning initiative backed by conservation NGOs and the government, designating specific areas for pastoralism and wildlife conservation, aiming to prevent further land subdivision and fencing.

- Community Conservancies – Encouraging neighboring Maasai landowners to collectively manage large tracts of land as wildlife conservancies, allowing eco-tourism and conservation incentives to generate sustainable income while maintaining migration corridors.

The Path Forward: Urgent Conservation Priorities

While these interventions have had some success, stronger policy enforcement and long-term conservation strategies are needed to secure the Athi-Kapiti ecosystem’s future. Key recommendations include:

- Legal Protection of Wildlife Corridors – Designating Kitengela and other dispersal zones as legally protected conservation areas to prevent further land fragmentation.

- Scaling Up the Wildlife Lease Program – Expanding financial incentives for more landowners to keep migration routes unfenced.

- Improving Infrastructure Planning – Implementing wildlife-friendly road crossings and underpasses to allow safe migration.

- Enhanced Community Engagement – Providing alternative livelihoods, such as eco-tourism and conservation employment, to reduce reliance on land sales.

The future of Nairobi National Park is directly tied to the preservation of these dispersal areas. Without urgent intervention, the park risks becoming an isolated ecological island, unable to sustain its diverse wildlife populations, ultimately diminishing one of Kenya’s most unique protected areas.

Most Common FAQs on the Athi-Kapiti Ecosystem

1. What is the historical significance of the Athi-Kapiti ecosystem?

The Athi-Kapiti ecosystem has historically been an important grazing land for the Maasai community and a wildlife-rich savannah landscape that has supported large mammal migrations for centuries. Early European explorers and settlers recognized its ecological value, and it has been a critical conservation area since the establishment of Nairobi National Park in 1946.

2. How does the Athi-Kapiti ecosystem contribute to Nairobi’s water supply?

The ecosystem plays a vital role in groundwater recharge and maintaining the ecological balance of rivers like the Mbagathi, which is a key water source for Nairobi National Park. Additionally, it helps regulate rainfall infiltration and prevents excessive surface runoff, reducing soil erosion and enhancing water retention in the region.

3. Why is the Kitengela migration corridor important for Nairobi National Park?

The Kitengela Wildlife Dispersal Area is a critical extension of Nairobi National Park, allowing seasonal migration of herbivores such as wildebeest, zebras, and hartebeest. Without this corridor, the park would become an ecological island, leading to overgrazing, genetic isolation of species, and an overall decline in biodiversity.

4. Are there private conservancies in the Athi-Kapiti region?

Yes, several private conservancies play a key role in conservation. Notable ones include:

- Kapiti Plains Research Station – Managed by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) for studies on livestock and wildlife coexistence.

- Olerai Conservancy – Focused on eco-tourism and wildlife protection.

- Enkop-Kitengela Conservancy – A community-driven initiative aiming to maintain open rangelands for wildlife.

5. How does livestock grazing impact the ecosystem?

Livestock grazing has both positive and negative effects. When managed sustainably, grazing by Maasai pastoralists helps maintain open grasslands and prevents bush encroachment. However, overgrazing due to increased settlement and land privatization leads to habitat degradation, reduced water availability, and competition with wildlife for resources.

6. What are the main predators in the Athi-Kapiti ecosystem?

The area supports a variety of predators, including:

- Lions – Primarily found in Nairobi National Park, with some venturing into Kitengela.

- Leopards – More elusive but present in rocky outcrops and wooded areas.

- Cheetahs – Occasionally seen in open plains.

- Spotted Hyenas and Jackals – Common throughout the ecosystem, often causing human-wildlife conflict.

7. Are there community-led conservation efforts in the region?

Yes. The Kitengela Wildlife Conservation Lease Program is one of the most notable initiatives, where local Maasai landowners receive financial incentives to keep land unfenced for wildlife movement. Other projects involve eco-tourism partnerships, tree planting initiatives, and sustainable land-use planning.

8. What role does the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) play in the ecosystem’s fragmentation?

The SGR, which runs through parts of the Athi-Kapiti ecosystem and Nairobi National Park, has significantly affected wildlife movement. Despite the construction of underpasses and viaducts to allow animal crossings, many species have avoided using them. Additionally, increased human activity and fencing along the railway route have further limited traditional migration routes.

9. How is climate change affecting the ecosystem?

Climate change is leading to more frequent droughts, erratic rainfall, and higher temperatures, affecting both wildlife and livestock. With less reliable water sources, animals are forced to move farther in search of food and water, increasing human-wildlife conflicts in settled areas.

10. What can be done to ensure the long-term survival of the Athi-Kapiti ecosystem?

- Stronger land-use policies to prevent uncontrolled urban expansion.

- Enhanced conservation incentives for landowners to maintain open rangelands.

- Improved infrastructure planning that accommodates wildlife corridors.

- Greater community engagement in conservation efforts.

- More sustainable tourism models that benefit local people and protect the environment.