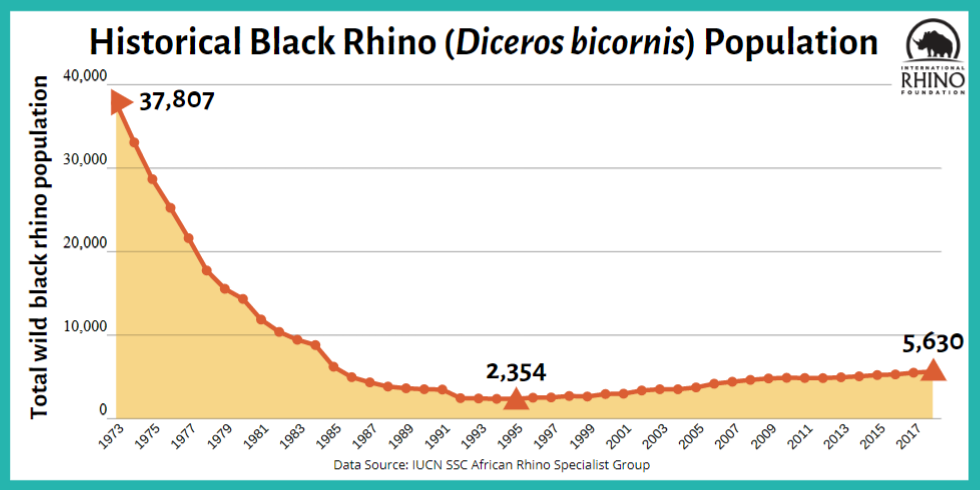

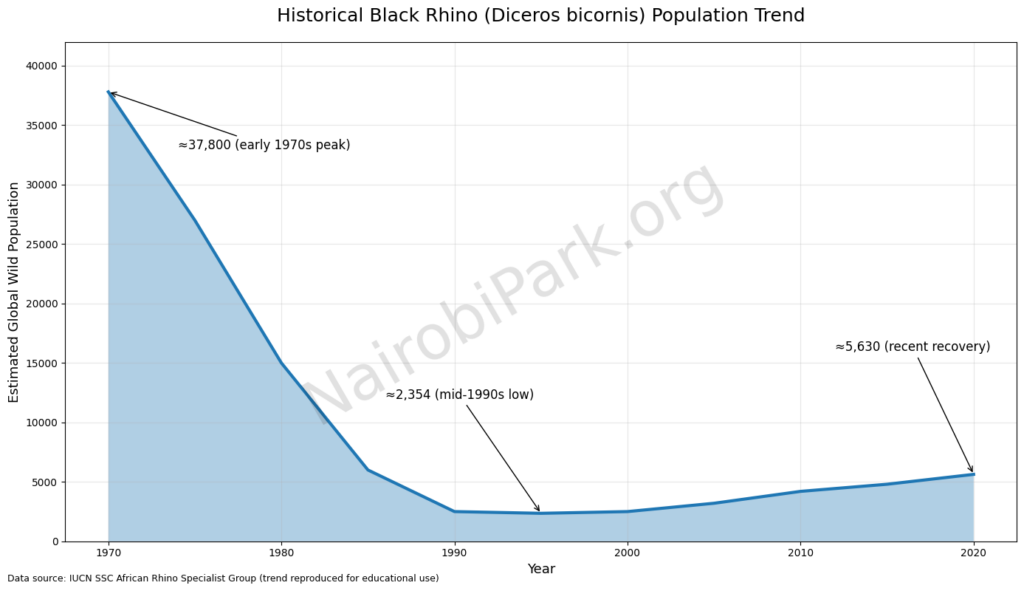

Nairobi National Park’s rhino conservation success story is part of the bigger success story of rhino population revival.

Kenya’s rhino recovery is not a single intervention. It is a 40-year conservation system built around intensive protection, sanctuary-based breeding, science-led population management, and carefully planned translocations—backed by national policy and sustained investment. The result is a widely cited comeback: Kenya’s black rhinos rebounded from a few hundred animals after the poaching crisis to 1,059 black rhinos and 1,041 southern white rhinos (plus the last two northern white rhinos) in recent national counts cited by major conservation organizations.

Below is a clear, end-to-end explanation of how the system worked, what changed over time, and the entity topics that make the story convincing and easy to follow.

1) The Crisis That Forced a New Model

The collapse

- By the late 1980s/early 1990s, Kenya’s rhinos had been devastated by poaching and illegal wildlife trade, leaving small, scattered “remnant” pockets of animals.

- Many surviving rhinos outside secure areas became “outliers”: isolated individuals in remote, hard-to-protect zones—difficult and costly to locate, monitor, or capture. (This is a key point in R.A. Brett’s 1990 sanctuary analysis.)

The policy response

- Kenya adopted a national shift toward a Rhino Conservation Programme and sanctuary strategy following the poaching crisis, including explicit high-level political support for structured rhino conservation.

2) The Sanctuary Strategy (The “Kenyan Model”)

Kenya’s signature approach—described in classic sanctuary literature like Brett (1990) and reinforced in later program summaries—is best understood as concentrated security + concentrated biology:

2.1 Consolidate rhinos into secure sanctuaries

- When poaching peaked, Kenya moved remaining rhinos into fenced or intensively protected sanctuaries where they could be guarded and managed more effectively.

- This model reduced exposure by shrinking the “security problem” from vast landscapes to defensible management units.

2.2 Manage sanctuaries like breeding engines (not static museums)

Brett (1990) describes the objective clearly: build up rhino numbers as quickly as possible inside secure areas, then use surpluses to restock former range.

Key management ideas that became standard:

- Carrying capacity (ECC) estimates for enclosed sanctuaries and management levels below maximum capacity to sustain breeding and avoid habitat collapse.

- Active population management once densities rise: remove surplus rhinos to maintain breeding performance and reduce conflict.

This is the foundation for why Kenya’s modern rhino work looks “hands-on”: it is designed that way.

3) Security: Why Kenya’s Approach Worked When Many Failed

3.1 Intensive, specialist protection units

- Kenya built rhino protection capacity inside priority sites, including dedicated rhino monitoring and protection units (for example, Nairobi National Park’s rhino unit is explicitly recognized by KWS).

3.2 A national deterrence signal

- Kenya has repeatedly used high-profile actions to communicate that wildlife products have no legitimate value (e.g., destruction of ivory and rhino horn stockpiles at Nairobi National Park).

Security is not one tactic—it is layered: patrols, intelligence, monitoring, rapid response, and visible national commitment.

4) Science-Led Population Management: The “Biology” Half of the Model

Sanctuaries succeed only if populations are managed, not merely protected.

4.1 Demography: sex ratio, age structure, and breeding performance

Brett (1990) highlights practical constraints that directly affect reproduction:

- Male-biased populations can depress birth rates.

- In small enclosed areas, dominant males may monopolize breeding, reducing effective population size even if headcount rises.

- High densities can increase aggression and mortality; breeding can decline when systems exceed ecological limits.

These are management realities Kenya learned early and addressed through translocation, stocking plans, and periodic redistribution.

4.2 Metapopulation management

A major conceptual leap described in sanctuary literature is managing Kenya’s rhinos as a metapopulation (linked subpopulations), not isolated herds:

- Establish new populations with enough unrelated founders.

- Periodically move unrelated animals between populations to protect genetic variability.

- Use monitoring and population viability approaches to guide decisions.

This “system management” is one reason Kenya’s recovery is seen as durable rather than accidental.

5) Monitoring, Identification, and “Law Enforcement Biology”

Modern rhino conservation works because every rhino becomes a monitored conservation asset.

What “monitoring” really means

- Individual identification (horn shape, scars, behavior; and in many contexts, structured ID systems).

- Routine checks on body condition, injuries, calf survival, and spatial movement.

- Detecting stress signals early (e.g., unusual roaming or boundary pressure).

Notching as a protection tool

Kenya has used large-scale rhino notching exercises as part of its security and monitoring system—both to support identification and to deter poaching by making horn less “clean” for illicit trade chains.

6) Translocation: The Tool That Turned Sanctuaries into Range Expansion

6.1 Why Kenya translocates rhinos

Translocation is central to Kenya’s success because it allows managers to:

- reduce density and conflict in crowded sanctuaries,

- seed new populations in secure landscapes,

- correct sex ratio or genetic constraints,

- restore rhinos to areas where they were wiped out.

A high-profile recent example is the relocation of 21 eastern black rhinos to Loisaba Conservancy, explicitly framed as moving rhinos from overcrowded parks including Nairobi National Park to restore range and improve breeding prospects.

6.2 Translocation is also a risk event (and Kenya learned this publicly)

Kenya has experienced serious translocation setbacks (e.g., the widely reported 2018 Tsavo East losses), which triggered scrutiny and an emphasis on improved protocols, habitat checks, and transparency.

The credibility of Kenya’s success story is stronger when this is acknowledged: Kenya’s programme improved by confronting failure, not denying it.

7) Range Expansion at Scale: Tsavo as the “Next Chapter”

Kenya’s strategy increasingly focuses on creating large secure rhino landscapes, not just small fenced pockets.

Tsavo West expansion (Ngulia legacy → large secure landscape)

- KWS has announced/outlined a major expansion in Tsavo West‘s Ngulia Sanctuary framed as opening the world’s largest rhino sanctuary landscape, explicitly linked to the historic collapse and the subsequent creation of KWS-era conservation.

- Conservation organizations describe the expanded Tsavo West rhino sanctuary landscape at ~3,200 km² and note that it consolidates rhinos from Ngulia and other sources into a larger secure system.

This matters for “how success works”: once sanctuaries breed rhinos, you must create new secure space or you hit carrying-capacity ceilings.

8) The Institutional Ecosystem Behind the Success

Kenya’s rhino recovery is often credited to a recognizable ecosystem of entities:

Government leadership

- Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS): statutory authority managing protected areas and leading security, monitoring, and policy implementation.

Conservation NGOs and partnerships

- African Wildlife Foundation (AWF): describes the sanctuary consolidation approach and ongoing protection mechanisms.

- Save the Rhino: documents private and community rhino sanctuary ecosystems and the threat context (poaching pressure, insecurity) that shaped Kenyan responses.

International standards and accountability

- IUCN/SSC African Rhino Specialist Group reporting and broader African rhino frameworks provide continental context on trends, poaching pressure, and recommended approaches.

9) Why Kenya Is “Lauded” as a Success Story (What Actually Earned That Reputation)

Kenya’s rhino programme is widely respected because it achieved three difficult outcomes simultaneously:

- Stopped the slide by consolidating protection into defensible sanctuaries.

- Rebuilt numbers into a nationally significant population—now cited at ~2,102 rhinos total (black + southern white + northern white).

- Evolved into expansion: shifting from “save what’s left” to “create new space and redistribute rhinos,” including major projects like Loisaba and Tsavo landscape expansion.

Nairobi National Park’s Role in Kenya’s Rhino Conservation Story

Early Rhino Refuge

Nairobi National Park was one of Kenya’s earliest securely protected rhino areas, safeguarding breeding populations well before the formal “rhino sanctuary” model was established. This early protection proved critical when poaching intensified elsewhere.

Proof of the Sanctuary Model

The park demonstrated that small, intensively managed areas could successfully protect and grow rhino populations—shaping Kenya’s later nationwide sanctuary strategy.

Source Population for Expansion

As numbers recovered, Nairobi National Park became a donor site, contributing rhinos to other sanctuaries through controlled translocations and supporting national range-expansion goals.

Operational & Security Advantage

Its proximity to Nairobi enabled rapid veterinary care, intelligence gathering, and security response under Kenya Wildlife Service, setting operational standards later applied in other rhino sanctuaries.

Lessons in Population Management

Long-term monitoring at Nairobi highlighted the importance of carrying capacity, territorial conflict, and breeding suppression, reinforcing the need for periodic translocation and meta-population planning.

National Conservation Signal

Nairobi National Park’s success provided visible proof that sustained investment works—helping secure policy support and funding for Kenya’s broader rhino recovery programme.

In essence: Nairobi National Park functioned as an early refuge, testing ground, and breeding engine, playing a pivotal role in transforming Kenya’s rhino conservation from crisis management into a long-term recovery success.

Read about all Conservation Efforts at Nairobi NP