Nairobi National Park is often described as a “wildlife park next to a capital city,” but ecologically it is not a standalone unit. Its long-term integrity depends on whether wildlife can still disperse south into Kitengela and the wider Athi–Kaputiei Plains—the historic wet-season grazing and calving landscape that prevents the park from becoming an over-compressed, fenced “island.” When that southern permeability breaks down, research consistently shows the same cascade: migratory grazers decline first, predator–prey dynamics destabilize, human–wildlife conflict rises, and the park’s ecosystem function simplifies over time.

This guide follows the full outline you provided and synthesizes what the research says about corridor ecology, land-use change, observed wildlife declines, and the main conservation instruments—especially the Kitengela Wildlife Conservation Lease (WCL) model and the policy choices required to keep the corridor open.

What Is Kitengela in Relation to Nairobi National Park?

Definition of the Kitengela Dispersal Area

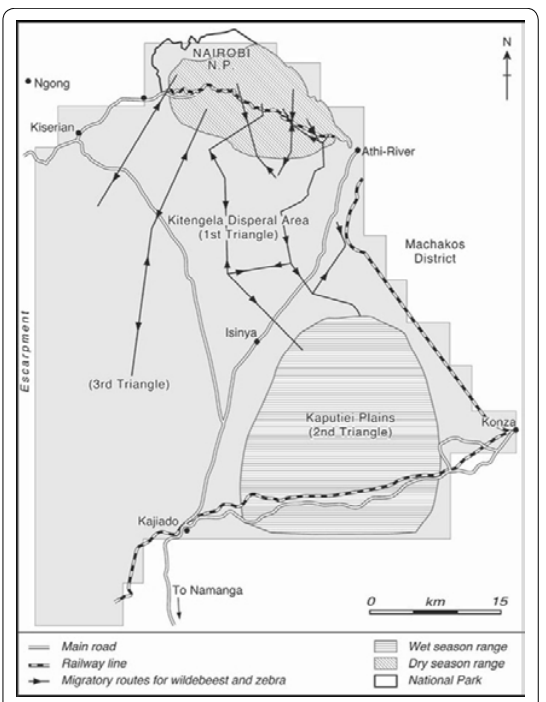

Kitengela Dispersal Area refers to the rangelands immediately south of Nairobi National Park that wildlife uses seasonally—especially in wetter periods—when forage quality improves outside the park and when calving space and grazing buffers are needed beyond the fenced core. Because most of Nairobi National Park’s perimeter is fenced, the open southern interface with Kitengela functions as the park’s last major ecological outlet.

What is a wildlife dispersal area?

A dispersal area is land outside a protected area that wildlife uses to spread out (disperse) for grazing, breeding, and movement. It reduces density pressure inside the protected core and supports seasonal resource tracking.

What is a migratory corridor?

A migratory corridor is the set of movement pathways and permeable habitat blocks that allow animals to travel between seasonal ranges (e.g., dry-season refuge to wet-season grazing/calving areas). Corridors are not just “lines on a map”—they are functional landscapes that must remain sufficiently open (low fencing, low settlement blockage, compatible land uses) for movement to remain viable. Read more about Animals at Nairobi National Park

Why Kitengela is ecologically different from the park core

- Park core (NNP): fenced protected nucleus; reliable refuge; constrained space; high edge effects.

- Kitengela rangelands: privately/communally managed multi-use landscape; wet-season forage and movement space; higher exposure to fencing, subdivision, cultivation, and settlement.

That difference matters because Nairobi National Park’s size and fencing mean it cannot replicate the full seasonal habitat portfolio needed by mobile grazers without access to the southern rangelands.

Geographic Position Within the Athi Kaputiei Ecosystem

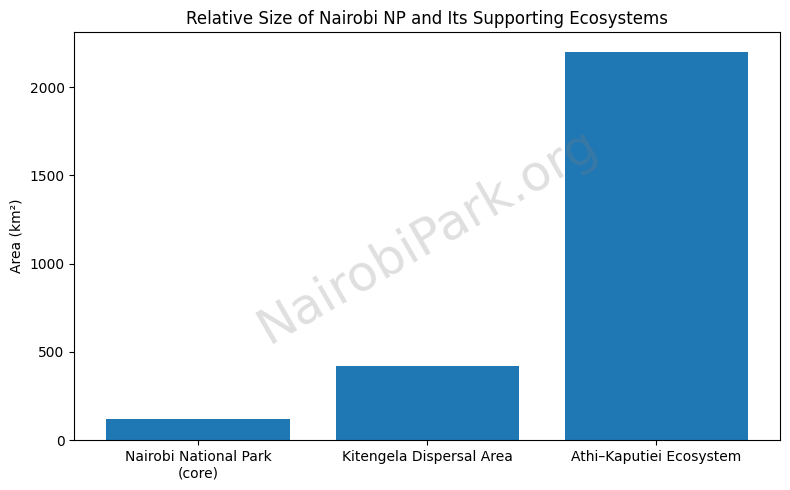

Researchers describe the system in nested ecological layers:

- Nairobi National Park: ~117 km² protected core.

- Kitengela rangelands / dispersal area: often described in the ~390–450 km² range depending on boundary definitions used by different studies.

- Athi–Kaputiei Plains (wider ecosystem): commonly cited around ~2,200–2,500 km² as the broader seasonal range context.

How ecosystem layering works (why the scale matters):

A small protected core can hold wildlife, but it cannot sustain natural population processes (mobility, calving dispersion, drought tracking, grazing rotation) if the surrounding seasonal range collapses. The larger the mobility requirement of a species, the more it depends on the broader ecosystem beyond the fence.

Why Nairobi National Park Cannot Function as an Ecological Island

- Fence boundaries: fencing concentrates wildlife, reduces escape options, and increases edge conflict risk—especially when the only open side is being urbanized.

- Historical migration routes: the park historically functioned as a refuge within a much larger rangeland system; wildlife moved with rainfall and forage dynamics.

- Seasonal mobility logic: mobility is an ecological “pressure release valve.” When it is blocked, range compression becomes the dominant driver of decline (first grazers, then wider food-web effects).

Historical Wildlife Movement Between Kitengela and Nairobi National Park

Wet Season and Dry Season Range Shifts

Dry season: the protected park core can function as a refuge when grazing outside becomes limited or risky.

Wet season: wildlife historically dispersed south into Kitengela/Athi–Kaputiei where fresh grass flushes and calving space expands.

Key ecological drivers:

- Calving zones: many grazers need broader, safer open plains and adequate forage to support calving and lactation.

- Forage distribution: rainfall gradients shift forage quality and quantity across the landscape.

- Predators follow prey: lion space use and hunting opportunities track prey density—so prey compression changes predator behavior and conflict profiles.

Migration Patterns of Key Species

Examples repeatedly discussed in the literature:

- Wildebeest (key migration-sensitive grazer)

- Zebra (mobile grazer, often moves with forage)

- Buffalo (uses broader habitat mosaics; movement affected by water/forage and disturbance)

- Lions (movement and conflict exposure strongly linked to prey distribution and livestock interfaces)

What Changed Over the Past 40 Years

Multiple analyses converge on a large decline in migratory grazers in the wider ecosystem—particularly wildebeest—coinciding with land subdivision, fencing, cultivation, and settlement growth in former dispersal ranges. For instance, one widely cited ecosystem analysis reports major reductions in wildebeest numbers between late-1970s baselines and later counts, consistent with a long-run collapse of migratory function.

Mechanistically, the “what changed” story is straightforward:

- Access to wet-season range shrank.

- Movement routes became fragmented.

- Calving access and grazing buffers declined.

- The system increasingly behaved like a compressed, edge-conflict-prone remnant around a fenced park.

Land Use Change in Kitengela: Satellite Evidence and Ground Reality

Grassland Loss and Vegetation Conversion

Remote sensing and land-cover assessments describe a decisive conversion trend away from rangeland toward built environment and agriculture.

One study reports (1984 → 2010) changes including:

- Grassland: −54.13% (approx. 174.94 → 80.24 km²)

- Riverine vegetation: −81.63% (approx. 211.18 → 38.79 km²)

- Built-up / tarmac: +261.40% (approx. 15.26 → 55.15 km²)

- Farmland: +18,495.24% (approx. 0.21 → 39.05 km²)

Interpretation (ecology, not just land-cover):

- Less grassland = less wet-season grazing capacity and fewer open movement options.

- Less riverine vegetation = weaker habitat quality and drought buffering along key pathways.

- More built-up and farmland = more fences, more conflict triggers, lower permeability.

Fencing and Subdivision

Kitengela’s land-tenure changes—especially subdivision and fencing—create corridor bottlenecks (narrow movement pinch points) where permeability can fail even if some habitat remains.

Commonly cited drivers:

- Group ranch fragmentation into smaller parcels

- Boundary fencing (including electrified fencing)

- Plot-level cultivation and structures that physically block movement

Industrial and Urban Expansion Pressures

Pressures are amplified by proximity to Nairobi and growth nodes including:

- Athi River industrial expansion

- Residential growth (Kitengela–Ongata Rongai–Kiserian axis)

- Infrastructure barriers that increase fragmentation and speed conversion pressure

Wildlife Confinement and Ecological Compression

What Happens When Migration Routes Close

When permeability declines, the ecosystem fails through range compression:

- Forage competition increases inside/near the park boundary.

- Calving disruption increases when animals cannot reach suitable calving landscapes.

- Predator stress and instability rise as prey distributions become unnaturally concentrated and edge-exposed.

Human Wildlife Conflict Escalation

As wildlife is pushed against human settlement edges:

- Livestock predation risk rises.

- Crop damage and property incidents increase.

- Retaliatory killings become more likely in high-friction zones.

Statistical Signals from Ecosystem Studies

Socio-ecological studies in Kitengela commonly report:

- stakeholder-rated impacts where loss of migratory routes, loss of dispersal areas, and wildlife confinement are ranked among the most important effects of land subdivision; and

- statistical tests linking land-use/tenure dynamics with perceived migratory wildlife declines (with typical caveats: multiple interacting drivers, complex system noise).

The Wildlife Conservation Lease Program: Incentive-Based Corridor Protection

Origins of the Kitengela Land Lease Model

The Kitengela Wildlife Conservation Lease / Wildlife Conservation Lease Program (WCL) is widely described as starting around 2000 as a direct-payment mechanism to keep key parcels open and unfenced so wildlife movement remains possible.

Core design logic:

- Corridor land is largely privately/communally controlled.

- Without incentives, conversion pressure makes fragmentation rational for landowners.

- Payments can maintain permeability while supporting livelihoods.

Conditions and Compliance Requirements

Typical lease conditions described in evaluations include commitments such as:

- land remains unfenced

- no cultivation

- no permanent structures

- wildlife-compatible grazing and retention of indigenous vegetation

Reported Outcomes and Household Impact

Reported program scale and livelihood impacts (as summarized in published evaluations):

- meaningful acreage enrolled (often cited around corridor-scale targets in the tens of thousands of acres) and hundreds of participating households;

- household cashflow contributions that can be especially important during drought years;

- education spending is frequently highlighted as a dominant household use of lease income.

Limitations and Funding Gaps

Recurring limitations noted across evaluations:

- Payment competitiveness: lease rates must compete with subdivision and development opportunity costs.

- Development pressure: urban expansion can outbid conservation payments.

- Continuity challenges: corridors fail if gaps form; connectivity is only as strong as the weakest bottleneck.

Policy, Planning and Zoning in the Kitengela–Athi Kaputiei System

Physical Development Planning

A corridor cannot be protected by payments alone if planning frameworks allow unregulated fragmentation at the bottlenecks. Priority governance actions typically include:

- zoning enforcement in identified corridor blocks,

- explicit corridor mapping into planning instruments,

- development controls near non-negotiable movement pathways.

Conservation Easements and Long-Term Instruments

Where feasible, long-term tools can reduce repeated renegotiation costs:

- conservation easements (or functionally similar instruments)

- longer-duration lease structures

- negotiated land-use covenants aligned to corridor integrity

Corridor Governance and Stakeholder Engagement

Corridor governance is multi-actor by nature:

- community landowners and user groups

- county/national government planning and enforcement

- NGOs and conservation finance partners

- park management and adjacent institutions

Effective governance aligns incentives, planning rules, and conflict response capacity.

Implications for Safari Tourism and Game Viewing

How Corridor Fragmentation Affects Wildlife Density

There is an uncomfortable paradox:

- Short-term visitor experience can become more predictable because animals are increasingly confined near core circuits.

- Long-term ecosystem viability declines because confinement is a symptom of collapsing mobility and rising edge stress.

Half-Day Safari Impact

Range compression can improve half-day “hit rate” because:

- animals are closer to established circuits,

- grazing herds are more consistently present,

- predator sightings can become more frequent near prey concentration zones (though never guaranteed).

Full-Day Safari Experience

Full-day drives still add value by allowing:

- deeper habitat sampling (riverine edges, woodland transitions, southern boundary dynamics),

- better odds for rarer species that require time and patient routing,

- more behavioral observation (not just “tick-list” sightings).

Long-Term Risk to Tourism Value

If corridor function collapses, long-run tourism value is threatened by:

- loss of seasonal movement dynamics,

- simplified species assemblages,

- higher conflict-driven mortality and instability,

- reduced resilience to drought and climate variability.

Local Access and Travel Considerations

Distance and Access from Kitengela

Travel times vary with traffic, but key planning realities are:

- Nairobi National Park is immediately north of the Kitengela rangelands system; access depends on which side you’re approaching from and which gate aligns with your route.

- Gate choice should minimize city cross-traffic if you’re starting from the south.

Accommodation Near the Corridor

Accommodation demand is heterogeneous (business commuters, city visitors, safari stopovers). Practical guidance:

- If your priority is early entry, stay closer to the park access routes that avoid CBD congestion.

- If your priority is corridor context, stay southward and plan a dawn departure.

Kitengela Day Trips to Nairobi National Park

Planning principles:

- Start early for wildlife activity and to reduce traffic risk.

- Use a defined routing plan (rhino circuits early; plains loops for grazers; riverine edges later).

- If combining with other attractions (e.g., conservation visits), protect fixed time windows first.

The Future of the Nairobi National Park Ecosystem

Ecological Projections if Corridors Close

The core risk is functional isolation: the park becomes a fenced remnant unable to sustain natural mobility-driven processes. Research on similar systems indicates that migration-sensitive herbivores are typically the first to collapse, with downstream impacts on predators and vegetation dynamics. The direction of change is well-supported: reduced permeability → compression → decline.

If you are using a policy-facing claim like “>50% decline over 30 years,” treat it explicitly as a scenario risk estimate unless you can tie it to a specific published model for the Athi–Kaputiei system. The evidence base strongly supports substantial decline risk under continued fragmentation; precise percentages should be sourced to a named projection study if you publish a numeric forecast.

Scaling Corridor Solutions

What “scale” means in practice:

- Lease expansion to eliminate connectivity gaps and protect bottlenecks.

- Funding mechanisms that track opportunity costs (payments must remain competitive).

- Conservation finance innovation (blended finance, tourism-linked corridor funds, verified outcomes-based models) anchored in enforceable land-use commitments.

Citizen-Led Conservation and Stakeholder Collaboration

A durable corridor strategy typically requires:

- community-negotiated agreements that are financially credible,

- transparent governance and monitoring,

- reinvestment pathways that make local benefits legible and dependable,

- public engagement that links visitor value to corridor survival.

NairobiPark.org’s role in protecting Nairobi National Park (with a Kitengela corridor focus)

- Translate corridor science into decision-ready public guidance. We publish plain-language, evidence-led explainers that connect Kitengela dispersal function → migratory decline → conflict → tourism value, so visitors and residents understand why the park cannot survive as a fenced “island.”

- Keep the Kitengela solution set visible: leases, land-use planning, and corridor continuity. We document the logic and performance of the Wildlife Conservation Lease (land-lease) model (launched in 2000) and explain why corridor permeability is the key conservation bottleneck—not an optional add-on.

- Anchor public education to the park’s own management priorities. We point readers to (and operationalize) management-plan realities—so discussions about wildlife, infrastructure, and tourism are framed around an ecosystem plan, not just trip planning.

- Mobilize citizen-backed pressure for corridor protection. Our petition and advocacy messaging focus attention on the urgency of connectivity loss and the need for practical corridor instruments (leases, zoning enforcement, and stakeholder alignment).

- Build a pro-conservation coalition around the “NNP ecosystem,” not just the park fence. We actively promote and connect people to conservation groups (e.g., Friends of Nairobi National Park) to grow participation, funding attention, and accountability for corridor outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions About Kitengela and Nairobi National Park

Is Kitengela part of Nairobi National Park?

No. Kitengela is largely outside the protected boundary. Ecologically, it functions as the park’s most important dispersal landscape and corridor system.

Why is the southern corridor important?

Because it is the main remaining pathway that allows seasonal movement, reduces density pressure, and supports calving and wet-season foraging beyond the fenced core.

Can wildlife survive without Kitengela?

Some wildlife will persist in the park core, but the system becomes increasingly compressed and less ecologically complete. Migration-sensitive herbivores are most at risk, with ripple effects across predators and conflict.

How does land subdivision affect migration?

Subdivision commonly increases fencing, cultivation, and structures—creating physical barriers and bottlenecks that reduce permeability and increase edge conflict.

What is the conservation lease program?

A direct-payment model that compensates landowners to keep land open and wildlife-compatible (e.g., unfenced, uncultivated), maintaining corridor function.

Is the corridor permanently protected?

Not inherently. Lease-based systems require sustained financing and strong governance; long-term security usually needs planning instruments and/or durable legal protection tools.

How does this affect safari visitors?

In the short run, confinement can raise sighting predictability; in the long run, ecosystem simplification and instability reduce the quality and integrity of the wildlife experience.

How Kitengela’s Changing Land Use Affects Game Viewing in Nairobi National Park

Nairobi National Park does not function as a closed ecosystem. Its wildlife depends heavily on the Kitengela Dispersal Area to the south for seasonal movement, grazing, and calving. As land use in Kitengela has changed over recent decades—through subdivision, fencing, farming, and urban expansion—the patterns of wildlife presence inside the park have also changed, with direct implications for game viewing.

1. Wildlife Is More Confined to the Park Core

As traditional migratory routes and dispersal areas in Kitengela have been blocked, many species are less able to move freely south during the wet season. Research shows that wildlife confinement within or near the park has increased as access to former ranges (including wildebeest calving areas) has declined.

What this means for visitors:

- Animals are more consistently present inside the park year-round

- Sightings are less dependent on perfect timing or season

- The park increasingly behaves like a high-density refuge, especially for grazers

Impact on Half-Day Game Drives (4–5 hours)

Half-day tours benefit significantly from these changes.

Why half-day drives now work better than before:

- Wildlife is closer to main game-drive circuits

- Large mammals (zebra, buffalo, giraffe, wildebeest) are often encountered within the first 1–2 hours

- Carnivores such as lions are more frequently seen near southern and central plains, where prey concentrates

Practical result:

A morning or afternoon half-day safari now delivers a high probability of quality sightings, even for visitors with limited time—making Nairobi National Park one of the most reliable urban-edge safari experiences in Africa.

Impact on Full-Day Game Drives (8–12 hours)

Full-day tours still offer advantages, but the value has shifted.

What full-day drives now offer:

- Greater chance to observe predator behavior, not just presence

- Time to explore peripheral habitats (riverine areas, woodland edges, southern boundary zones)

- Better odds for leopard, cheetah, hyena, and extended lion interactions

What has changed compared to the past:

- You are less likely to see large-scale seasonal migrations within a single day

- Wildlife movements are more localized, not expansive across open plains

- Viewing is excellent, but less dynamic than in fully open ecosystems like the Mara

Bottom line:

Full-day drives now emphasize depth of experience rather than geographic coverage.

Seasonal Differences Are Less Extreme Than Before

Historically:

- Wet season: Wildlife dispersed widely into Kitengela

- Dry season: Animals concentrated inside the park

Today:

- Seasonal contrast is reduced

- Even in wet months, many animals remain inside or near the park

- This improves predictability for visitors year-round

Species-Level Effects Visitors Notice

More reliably seen:

- Plains zebra

- Wildebeest

- Cape buffalo

- Masai giraffe

- Lions

Seen, but requiring patience or a longer drive:

- Leopards

- Cheetahs

- Serval and other small carnivores

Why:

Confinement increases prey density (good for lions) but reduces open hunting space for wide-ranging predators like cheetah. See all animals at NNP here.

Trade-Offs Visitors Should Understand

Positive for game viewing

- Higher wildlife density

- Shorter drives to first sightings

- Excellent results for short visits and stopovers

Negative for ecosystem health

- Reduced migration and calving success

- Higher competition for forage

- Increased human–wildlife conflict pressure at park edges

This is why conservation incentives—such as the Kitengela Land-Lease Program—are critical not just for wildlife survival, but for maintaining high-quality game viewing in Nairobi National Park.

Visitor Takeaway

- Short on time? A half-day safari now delivers excellent value.

- Wildlife enthusiast? A full-day drive offers deeper ecological insight and better predator chances.

- Either way: Today’s strong sightings are directly linked to Kitengela’s shrinking openness—making land conservation outside the park essential for the future of Nairobi’s safari experience.

Below are some helpful resources:

- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Migratory-Wildlife-Confinement-due-to-Barriers-Caused-by-Increased-Human-Settlement_fig2_333810342

- Analysis of Impacts of Land Use Changes in Kitengela Conservation Area on Migratory Wildlife of Nairobi National Park, Kenya

- Direct payments as a mechanism for conserving important wildlife corridor links between Nairobi National Park and its wider ecosystem: The Wildlife Conservation Lease Program

- Wildlife Conservation Leases are Considerable Conservation Options outside Protected Areas: The Kitengela – Nairobi National Park Wildlife Conservation Lease Program

- Conservation in Kitengela – Policy Brief