Nairobi National Park is one of the world’s most extraordinary conservation landscapes: a fully functioning savannah ecosystem set against the skyline of a rapidly growing capital city. Lions hunt within sight of office towers, rhinos graze near highways, and migratory herbivores move along corridors that intersect with human settlement.

This proximity creates a conservation reality unlike that of any remote wilderness. Effective management here is not only about wildlife protection, but about boundaries, coexistence, infrastructure, and responsible tourism. Understanding these dynamics gives visitors deeper context for what they see on half-day and full-day game drives—and why Nairobi National Park is as much a conservation laboratory as it is a safari destination.

Is Nairobi National Park Fenced?

Short answer:

Yes—partly. Nairobi National Park is fenced on the northern, western, and eastern sides, but it is intentionally open to the south to allow wildlife to move in and out of the park into the larger Athi–Kapiti ecosystem.

This makes Nairobi National Park one of the world’s most unusual protected areas: a fully functioning savanna ecosystem next to a major capital city, but not a closed ecological island.

Why Is Nairobi National Park Only Partly Fenced?

The fencing has two main purposes:

- Protect people and infrastructure

- The park borders Nairobi city, highways, residential areas, the airport, and industrial zones.

- Fences along the north, west, and east reduce:

- Human–wildlife conflict

- Wildlife straying into urban areas

- Poaching access points

- Accidents involving vehicles and trains

- Keep the southern ecosystem open for migration

- The southern boundary is unfenced by design.

- This allows animals—especially wildebeest, zebra, eland, hartebeest, and other grazers—to:

- Move seasonally between the park and Kitengela / Athi–Kapiti plains

- Access wet-season and dry-season grazing areas

- Maintain natural population dynamics

If the park were fully fenced, Nairobi National Park would become an ecological island, which would:

- Collapse seasonal migrations

- Increase overgrazing inside the park

- Increase inbreeding risk

- Reduce long-term ecosystem resilience

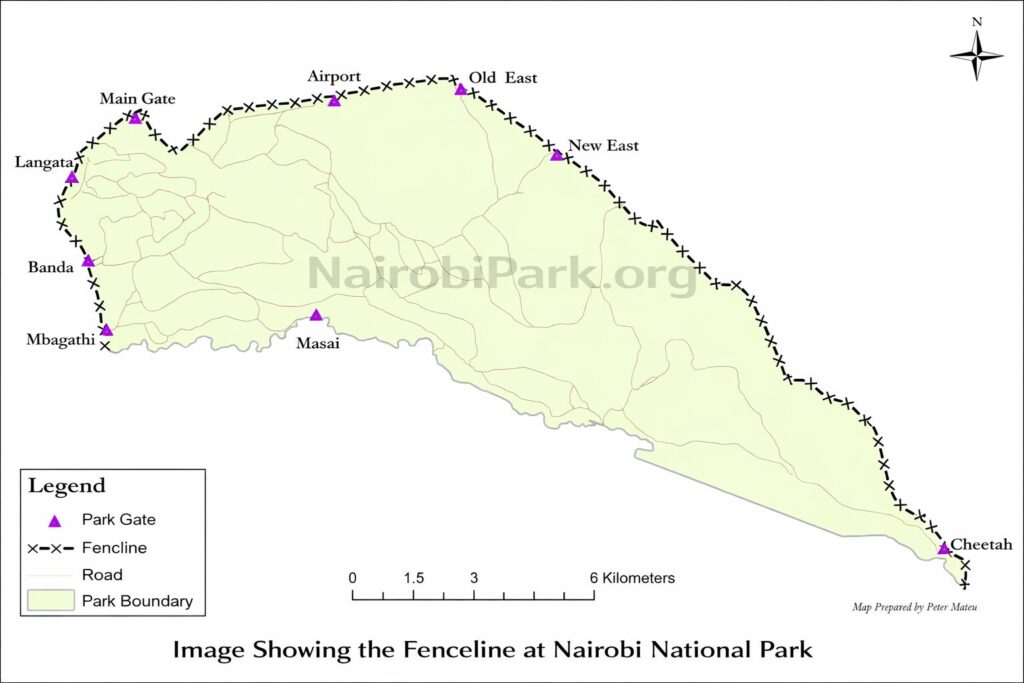

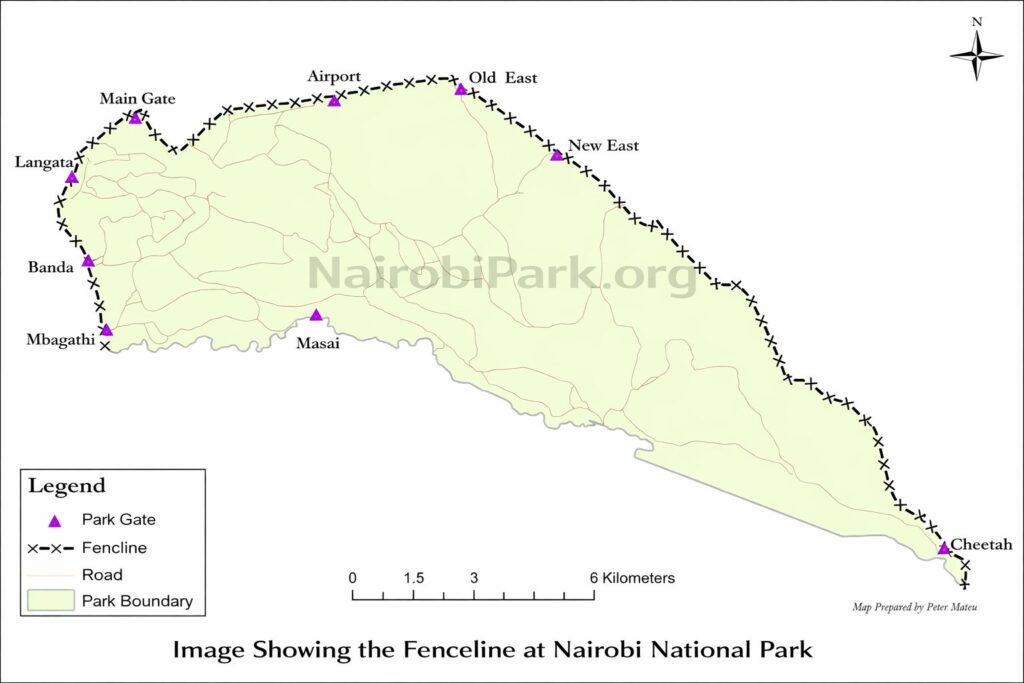

Where Exactly Is the Fence?

- North: Fully fenced (toward the city, Lang’ata, and Nairobi urban areas)

- West: Fenced (near Ongata Rongai and developed areas)

- East: Fenced (toward Embakasi, industrial zones, and infrastructure corridors)

- South: Open toward Kitengela, Isinya, and the Athi–Kapiti plains

The fence line follows a human–wildlife conflict minimization logic, not a simple geometric boundary.

What Type of Fence Is It?

- The fence is a wildlife-proof, reinforced barrier in most urban-facing sections.

- It is designed to:

- Stop large mammals like rhinos, buffalo, lions, and giraffes from entering the city

- Deter poaching incursions

- Reduce road and railway collisions

- In some sections, it includes:

- Chain-link fencing

- Reinforced posts

- Anti-dig and anti-climb features

- The fence is actively maintained by KWS (Kenya Wildlife Service), but breaches still occur due to:

- Floods

- Vandalism

- Infrastructure pressure

- Wildlife damage

Does the Fence Block Wildlife Migration?

Partly—but not completely.

- The southern side remains open specifically to allow migration and dispersal.

- However, outside the park:

- Land subdivision

- Fencing of private plots

- Urban sprawl

- Roads and railways

- Industrial development

…are progressively narrowing the available corridors.

So while the park itself is not fully fenced, the landscape around it is becoming functionally fenced by development.

This is why conservation efforts now focus not just on the park fence, but on:

- Wildlife corridors

- Conservation leases

- Land-use planning in Kitengela and Athi–Kapiti

Why Not Fence the Entire Park?

From a conservation science perspective, fully fencing Nairobi National Park would be a last resort and a sign of ecological failure, because:

- The park is too small (about 117 km²) to sustain healthy populations of:

- Wildebeest

- Zebra

- Eland

- Other migratory grazers

- Many species depend on seasonal movement to survive droughts and rainfall variability.

- A fully fenced park would:

- Turn migration species into resident populations

- Increase habitat pressure

- Force artificial population control (culling or translocation)

- Reduce genetic exchange

In short:

The open southern boundary is not a weakness—it is a core ecological feature of Nairobi National Park.

How Does This Compare to Other Parks in Kenya?

- Lake Nakuru National Park: Fully fenced (for rhino protection and containment)

- Nairobi National Park: Partly fenced, partly open (migration-dependent system)

- Amboseli National Park: Not fully fenced, relies on surrounding community lands

- Masai Mara National Reserve: Not fenced, but increasingly fragmented by development

Nairobi is unique because it sits inside a major city, making fencing necessary in some directions and disastrous in others.

Is the Fence Effective?

Yes—at what it is designed to do.

The fence has significantly:

- Reduced wildlife incursions into the city

- Reduced poaching access points

- Reduced road and rail accidents involving animals

But no fence can solve the bigger problem:

The long-term survival of Nairobi National Park depends more on what happens outside the fence than inside it.

That is why:

- Conservation leases in Kitengela

- Wildlife corridors

- Land-use planning

- Community conservation programs

…are now just as important as the fence itself.

The Big Conservation Reality

Nairobi National Park’s conservation challenge is not about fencing 117 km².

It is about financing, negotiating, and protecting a living ecosystem that extends far beyond the fence.

The fence protects the city.

The open south protects the ecosystem.

The future depends on whether the space between them remains open or disappears.

Why Nairobi National Park Is Fenced

Safety, coexistence, and modern conservation realities

Fencing in Nairobi National Park is primarily a human–wildlife coexistence measure. Unlike remote protected areas, the park directly borders residential neighborhoods, industrial zones, major highways, and transport corridors. In this context, fencing helps to:

- reduce the risk of human injury or fatalities caused by dangerous wildlife,

- limit livestock predation and crop damage in surrounding communities,

- reduce retaliatory killing and snaring of wildlife,

- support security for high-value and threatened species, particularly rhinos.

The fence is therefore best understood not as a barrier against nature, but as a management tool designed to balance wildlife protection with urban safety.

The ecological trade-off

From an ecological perspective, fencing always involves compromise. Large mammals historically moved freely between Nairobi National Park and the wider Athi–Kapiti ecosystem, particularly through the southern plains. Physical barriers can restrict:

- seasonal movement,

- genetic exchange,

- access to traditional grazing areas.

For this reason, fencing is one of the most debated conservation interventions in Nairobi NP. Park management must constantly weigh ecological connectivity against human safety and land-use change—a tension that defines conservation at the urban edge.

Human–Wildlife Conflict Around Nairobi National Park

What conflict looks like in practice

Human–wildlife conflict around Nairobi NP typically takes the form of:

- livestock predation by lions, hyenas, and leopards,

- crop damage by large herbivores such as buffalo,

- occasional close encounters that pose risks to people,

- and, in rare cases, retaliatory responses that threaten wildlife.

These conflicts are not driven by tourism or park mismanagement, but by land-use change—including settlement expansion, fencing of private land, and loss of dispersal space outside the park.

Why conflict has intensified

Several structural forces have increased pressure around Nairobi NP:

- rapid population growth in the greater Nairobi region,

- subdivision and privatization of former wildlife dispersal areas,

- infrastructure development that fragments open land,

- increased competition between wildlife and livestock for space and resources.

Fencing and targeted conflict-mitigation strategies are therefore part of a broader effort to prevent isolated incidents from escalating into systemic conservation failures.

Urban Infrastructure Pressure: Southern Bypass & SGR

4

Southern Bypass: edge effects and visual intrusion

The Southern Bypass runs along the southern edge of Nairobi National Park, introducing:

- noise disturbance,

- increased human activity at the park boundary,

- and visual intrusion into what was once open savannah.

To mitigate these effects, park management has emphasized buffering measures, including vegetation screening, to reduce disturbance and preserve the natural character of the park for both wildlife and visitors.

Standard Gauge Railway (SGR): fragmentation concerns

The construction of the Standard Gauge Railway near Nairobi NP has heightened awareness of how linear infrastructure can affect protected areas. Key conservation concerns include:

- habitat fragmentation,

- altered wildlife movement patterns,

- noise and vibration impacts,

- increased human access along infrastructure corridors.

While mitigation measures are incorporated into planning and management, these developments underscore the reality that Nairobi NP exists within a highly dynamic urban planning environment, where conservation outcomes depend on long-term governance and enforcement.

Rhino Protection Strategies in Nairobi National Park

4

Nairobi National Park is one of Kenya’s most important rhino conservation strongholds, supporting both black and white rhinos under intensive protection.

What “rhino protection” means on the ground

Rhino conservation in Nairobi NP relies on a combination of:

- continuous ranger patrols and intelligence-led anti-poaching operations,

- close population monitoring and individual identification,

- controlled access and rapid-response capability,

- integration of technology such as tracking and surveillance where needed.

These measures are coordinated by Kenya Wildlife Service, whose mandate includes balancing public access with the strict security requirements of a high-risk species.

Why fencing matters for rhinos

In an urban-adjacent park, fencing enhances rhino protection by:

- limiting unauthorized access points,

- reducing the risk of animals straying into unsafe areas,

- supporting faster response times in emergencies.

For visitors, this means rhino sightings in Nairobi NP are not accidental—they are the result of decades of sustained conservation investment.

Responsible Tourism: The Visitor’s Role in Conservation

Tourism in Nairobi National Park is not separate from conservation—it directly supports it. Park fees, regulated access, and professional guiding all contribute to maintaining security, infrastructure, and ecological monitoring.

Responsible behavior during half-day and full-day tours

Visitors can actively support conservation by following simple but important principles:

Wildlife viewing

- Keep noise low and movements calm.

- Allow animals to dictate the encounter; if behavior changes, create space.

- Never feed wildlife or attempt to attract attention.

Vehicle conduct

- Stay on designated tracks to prevent habitat damage.

- Avoid crowding sightings, particularly predators and rhinos.

- Minimize engine idling near animals.

Photography

- No flash photography.

- Prioritize ethical images over close proximity.

Conservation awareness

- Respect park rules as conservation tools, not inconveniences.

- Choose licensed operators and experienced driver-guides.

- Understand that access, timing, and fees are part of sustaining the park.

Why This Context Matters for Your Safari Experience

Nairobi National Park is not a “compromised” wilderness—it is a working conservation system under pressure, where success is measured daily. The presence of fences, roads, and city skylines does not diminish its ecological value; instead, it highlights one of the most important conservation challenges of the 21st century: how wildlife and cities coexist.

For visitors on half-day and full-day safaris, this context transforms a game drive into something deeper than sightseeing. Every lion sighting, every rhino encounter, and every open stretch of grassland represents an active conservation choice—made possible through careful management, community engagement, and responsible tourism.

On NairobiPark.org, this story is not an add-on. It is central to understanding why Nairobi National Park matters, and why visiting it responsibly helps ensure that wildlife continues to thrive on the edge of a growing global city.

FAQ on NNP Fencing

Is Nairobi National Park fully fenced?

No. It is fenced on three sides and open to the south to allow wildlife migration.

Why is Nairobi National Park not fully fenced?

Because many animals depend on seasonal migration into the Athi–Kapiti plains to survive.

Is the fence electric?

Some sections use reinforced wildlife-proof fencing; the design focuses on containment and deterrence rather than simple barriers.

Can animals leave Nairobi National Park?

Yes. They regularly move south into Kitengela and surrounding dispersal areas.

Will Nairobi National Park be fully fenced in the future?

Only if surrounding migration corridors collapse—something conservationists are actively trying to prevent.